The Pretty Woman

Genres ‘work on principles of repetitive conventions, and yet much of the time manage to reinvent themselves before reader exhaustion sets in. They would appear to resist social change and yet can provide a map of this, as well as sometimes exploring the possibilities for that change’. (Burton, 2010, p.27)

Genre is a French word that translates to 'type' or 'kind'. As genre films are frequently believed to be produced in Hollywood as systematic goods, a film critic's decision that a movie falls within a specific genre can be a means to denigrate the movie. The lowest of the low are thought to be romantic comedies. (McDonald, 2007)

Romantic comedy has proven to be one of cinema's most lasting genres. Its popularity has undoubtedly fluctuated at times, but like all the main genres, it has shown to be enduringly robust. Even today, audiences still like romantic comedy's basic structure and constituent parts. Even then, they are thought of as "guilty pleasures" that satisfy because they offer simple, straightforward simple pleasures. (Mortimer, 2010)

Not only romantic comedies but all genre films are perceived to offer uncomplicated possibilities for enjoyment due to their adherence to a known format. (McDonald, 2007)

The stereotypical romantic comedy is undoubtedly seen as a woman's movie; it may even be criticized by certain, frequently male, critics and categorized as a "chick flick." Undeniably, this unfavourable impression of the genre is not solely because it is sexist in nature; it has historically been the fate imposed on genre movies. Genre is about mass entertainment; it's about studios maximizing their earnings on their significant investment in a movie by copying successful formulas. In this sense, the genre has been considered as antithetical to innovation, artistry, and, consequently, critical worth. (Mortimer, 2010)

The underlying formula of repetition and difference is the essence of the genre. The romcom model has produced numerous intriguing and lucrative offshoots, as with other major genres, which continue to revitalize the form and draw in new viewers. As they borrow from and meld with other genres, these new directions push the boundaries of the genre's conventions while providing the audience with new pleasures. This is a group of viewers who have grown up with a long tradition of movies. They have easy access to media and films, and they appreciate the blending of many cinema genres, enjoying the known while looking for the unexpected. (Mortimer, 2010)

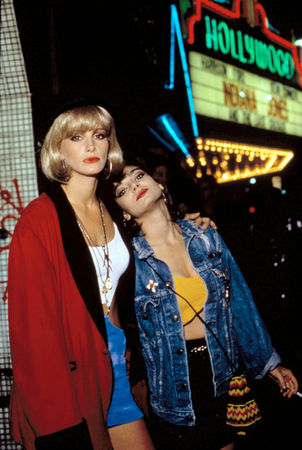

I find that ‘Pretty Woman’ best illustrates this statement. In Pretty Woman, by Garry Marshall, many imaginations come into play. It's a fairy tale about a poor Georgian girl who gets her happily ever after. It's a fantastical story about achieving success in Beverly Hills' salons and streets. It's a vision in which Roberts is transformed into a contemporary Audrey Hepburn, poised and graceful, and completely assured of her knowledge of the proper fork for each meal. (Tobias, 2020)

The plot of Pretty Woman centres on the relationship between Vivian Ward, played by Julia Roberts, a shrewd and alluring prostitute, and Edward Lewis, a shy but disconnected corporate tycoon played by Richard Gere. As Edward Lewis's company for a week, Vivian transitions from a Hollywood Boulevard prostitute to a stylish lady while negotiating the social labyrinth of Los Angeles society. Vivian's friendly and caring demeanour softens Edward, a stoic venture investor whose greatest talent is dismantling businesses and reselling them for enormous profits. Edward learns from Vivian the value of considering people when conducting business. Given their diverse socioeconomic origins, the pair encounters challenges along the road, but they are ultimately shocked to discover they are falling in love. The movie ends happily. (GS, n.d.)

We have to look no further than Pretty Woman to understand how Hollywood views women, a rags-to-riches narrative about a sex worker whose blurring of the boundaries between her business and her personal life fundamentally altered our perception of the elements that make up a great romantic comedy. (Cohen, 2020)

Many of those components—the shopping scene, the makeover, and the significant gesture—involve money, perhaps as a result of the transactional nature of the characters' relationship. The woman's actual self is shown, symbolized by Vivian's reddish-curly mane, which is untamed and raw. These are the more gendered elements. There's the first kiss, which is especially significant because, as a sex worker, it violates Vivian's principles for interacting with clients, proving she's truly in love. Until very recently, when fresh voices and viewpoints gave the rom-com its own makeover, the stereotype of a broken woman who is saved by her prince smacked of an antiquated version of relationships, which partially explains the genre's downfall in recent years. (Cohen, 2020)

Even if Pretty Woman has lost its rom-com appeal, it nevertheless merits a second viewing as a respectable piece of filmmaking that, among other things, raises important questions about men, women, sex, class, and power. When it debuted in theatres in 1990, it was divisive and the target of some nasty criticism.

Many of the predominantly male reviews highlight the movie's whimsy, which is a critique sometimes levelled at rom-coms because they are thought to appeal to women and are therefore considered less serious than, for example, a war drama. However, women also had problems with the movie, mostly because of the male gaze and the bland, appetizing way it handled prostitution: 'the hooker with the heart of gold'. (Cohen, 2020)

Undoubtedly, the business of prostitution is portrayed as being difficult, and Vivian is consistently discriminated against because of her commercial sex appeal, as seen when Edward refers to her as a "hooker" and when Phil assaults her. However, aside from this mistreatment, the portrayal of prostitution in the movie tends to be light-hearted or amusing. Early in the movie, Vivian escapes from her apartment by climbing out her window to avoid the landlord. Kit spends their rent money on drugs, although her character often serves as comic relief, and her troubles are handled with a knowing eyeroll and a smirk from her roommate, Vivian. Vivian's absorption into the elite is also frequently awkward and hilarious, but never actually forced. Even while she occasionally surprises her more affluent friends, class differences never amount to much more than a joke or an awkward situation. The street life's violence is frequently far away. Even "skinny Marie's" murder is dismissed by Kit as something she had coming to her, and the tourists who take a photo of the prostitute's body turn it into a comedic moment. The numerous tragedies and grim realities of sex labour are glossed over in the movie. Drug addictions, traumatic experiences, melancholy, and desperation are portrayed as amusing, which results in a fast-paced romantic comedy but a remarkably fanciful case study. (Jr., 1997)

Even yet, the movie struck a chord with viewers; it brought in approximately $500 million worldwide, making it a major hit that catapulted Roberts to fame, and subsequently made her the highest-paid woman in Hollywood and won her an Oscar nomination. Pretty Woman's success coincides with the emergence of a new female Hollywood icon. This is her movie; thus, it may also be ours. (Cohen, 2020)

The key ingredient in Pretty Woman's success is Julia Roberts' portrayal of the title role. The famously original title of the movie, 3,000, a reference to the amount of money exchanged between both the two protagonists was written by a man named J. F. Lawton. Had it not been for Roberts' charming star-making performance, the more jovial idea would not have been as snappy and consumable. It was a much darker version of the narrative, one that would have been more compelling and truer to life. (Cohen, 2020)

She is captivating right away in the first scene of her as Vivian Ward, filling in the toes of her battered stilettos with a black Sharpie before shimmying down the fire escape. Her big-mouthed, all-American grin, which illuminates every scene, is partially to blame. You want to laugh along with her when she laughs because she has the booming laugh of someone who gets every joke. You want to be Vivian's friend. We are all a little seduced, whether we are men or women, homosexual or straight. You can't help but be in her corner. (Cohen, 2020)

But the tale of a wealthy man who has lost his sense of purpose in life and discovers it in the embrace of a stunning, poor, down-to-earth woman with courage is as ancient as Hollywood. This business is responsible for the 1938 comedy Rich Man Poor Girl with Ruth Hussey and Robert Young. The tagline said, "How she become a millionaire." It is a story that is almost entirely associated with the romantic comedy subgenre, from Love Story to Working Girl to Maid in Manhattan. The Pygmalion dynamic, so famously depicted in 1964's My Fair Lady, served as the inspiration for Pretty Woman. (Cohen, 2020)

The fact that the female protagonist is a sex worker, someone whose metaphorical love is technically accessible to the highest bidder, distinguishes Pretty Woman from all the other movies mentioned above. She does make the overt claim that she is "clean" and responsible as she takes a cache of colourful condoms out of her boot. After each meal, she brushes her teeth with floss. She is not a virgin or a con artist like Anastasia Steele in Fifty Shades of Grey, who is captivated by expensive presents in the name of kindness and feeling. In such an unbalanced connection, the transactional element is obvious. In that regard, Pretty Woman is truly ground-breaking and more closely aligns with how some feminists currently view sex work. Why should Vivian be embarrassed as long as consent is given? Since rom-coms have always involved a trade of goods, why not have the money up front? (Cohen, 2020)

Nowadays, bringing up Pretty Woman brings up the change in perceptions of sex work. In the 33 years since its publication, a lot has changed. Many now argue that decriminalizing sex work is a feminist issue since it should be treated like any other job. Her infamous thigh-high boots, the defining fashion statement of a lady of the night, are today just as essential to any outfit as flats. The phrase "sex worker" itself serves as a symbol of that transition. The term "hooker," which is embarrassingly antiquated in today's context, is used quite freely in both Pretty Woman and its reviews. (Cohen, 2020)

However, the movie's other aspects are dreadfully constrained. The iconic, class-focused scenario in which Vivian visits the Rodeo Drive store that ignored her only makes sense in that situation. No matter how well-dressed she was, the salesperson's response would have been very different if she had been a lady of colour. This continues a tradition in pop culture that restricts the representation of sex work—and any other type of allegedly morally deviant behaviour—to acceptable white, acceptable attractive women. (Cohen, 2020)

The idea that a lady can be bought is another message that seems to be present throughout the film and is most blatantly illustrated in the shopping scene. It is immediately obvious who is holding the cards in this couple when Edward says that "Stores are never nice to people; they're nice to credit cards." Vivian needs his wealth to become more than just a nobody. The kind of woman that is irresistible to everyone — regardless of how independent, educated, and strong-willed she may be — is one that wears a designer name. In an oddly meaningful moment, the store manager remarks, "We have many things as beautiful as she would want them to be." But what precisely defines their beauty? The price. Vivian's body can be bought for a week by Edward for just $3,000. He will pay more for her heart and spirit, but not enough to fill more than a few shopping bags. (Wang, 2015)

While many still consider Pretty Woman to be one of the most memorable examples of a romantic comedy from the 1990s, some have criticized the movie for its portrayal of prostitution in Los Angeles, calling it variously unrealistic, spotless, glamorizing, and demeaning. It's interesting to note that the famous version of Pretty Woman was a reworking of a far grittier, and possibly more realistic, earlier draft of the script. There are several viewpoints in an article in Time titled "Here's What Former Sex Workers Think of Pretty Woman." While one prostitute who lived a hard life as a prostitute claims that "there are no Vivians," another sex worker who used sex work to pay for college thinks it accurately portrays someone who is taking advantage of the system to go up the economic ladder. The majority of people who have encountered prostitution concur that it is a much more brutal career route, one in which surviving comes before achieving a "fairy-tale ending." By implying that sex work is "low" or something to get away from, the movie demonizes it. Showing that Vivian feels confident in her career as a sex worker and establishes appropriate limits with the client, Edward, might give the impression that she is more powerful.

According to Heather M. Corcoran in Dazed, in addition to trivializing the risks associated with an illegal activity that frequently preys on weak individuals—mostly young women—the plot encourages the same notions that support the industry by maintaining sexual power dynamics firmly out of balance. He believes the movie reinforces the oppressive gender relations that sustain the seedier and more violent aspects of the prostitution industry while also negatively sanitizing it. Even though the movie tries to show Vivian as independent and driven, Corcoran thinks that by forcing her back into a relationship with Edward, the movie actually makes Vivian reliant on a man. The movie, in Corcoran's opinion, is hardly the feminist rom-com it claims to be. (Corcoran, 2015)

So, the movie's premise continues to be debatable. Without a doubt, a decent amount of suspension of disbelief is necessary. However, whether you like it or not, it has had a significant cultural impact. Although Vivian's clothing may be back in vogue, the gender relations in the movie most definitely are not. However, being aware of it and having that hindsight enables the audience to relax and simply enjoy something that we would feel we must criticize today. (Cohen, 2020)

There are many reasons to object to Pretty Woman's obscene consumerism and reactionary sexual politics, yet the soundtrack, which includes the Roy Orbison song that gave the film its title, is upbeat and the tempo is light. Gere is charming, and he and Roberts have a deft connection that makes you want to be a part of it. Vivian's ascent to the social elite is portrayed by Roberts as a triumph for the underdog. Happiness for her is as simple to feel as it is for a friend who wins the lottery. (Tobias, 2020)

References

Cohen, A., 2020. 30 Years Later, Pretty Woman Is So Much More Than A Guilty Pleasure, s.l.: s.n.

Corcoran, H. M., 2015. The dark reality of Pretty Woman. [Online] Available at: https://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/24246/1/the-dark-reality-of-pretty-woman

GS, n.d. Pretty Woman, s.l.: s.n.

Jr., C. J. S., 1997. Bodies and Minds for Sale: Prostitution in "Pretty Woman" and "Indecent Proposal". Popular Culture Association , Volume 19.

McDonald, T. J., 2007. Romantic Comedy Boy Meets Girl Genre. New York : Columbia University Press.

Mortimer, C., 2010. Romantic Comedy. s.l.:Routledge .

Tobias, S., 2020. The Guardian. [Online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/mar/23/pretty-woman-30-conservatism-materialism-glowing-star-power[Accessed March 2022].

Wang, C., 2015. Why Pretty Woman‘s Shopping Montage Is So Satisfying (& So, So Sexist), s.l.: s.n.